On an agents “wish list,” you found the term literary sitting among a hoard of genres. One genre, science fiction, describes your book. However, your story includes literary devices. It holds abstract ideas subject to interpretation. Your main character may fight alien peacekeepers, but he’s on an “internal,” coming-of-age journey. For those reasons, you think your work might be literary. And for that matter, isn’t every novel a literary work?

Research the difference between literary and genre. You might find yourself immersed in a sea of historical insight centuries deep. On the other hand, you may find a simple explanation: literary works are character driven; genre, plot driven. Regardless of how lengthy or complex the insight is, it still might leave you scratching your head.

Why the confusion?

Likely because all fiction is literature, hence literary. And literary works fall into genre categories.

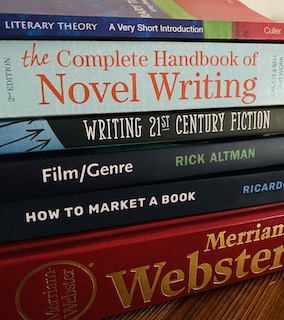

In Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction, Jonathan Culler qualifies the literariness of a work. This is necessary because directions, history books, and other written copy are considered literature. Ultimately, he concludes this:

- Literary describes fiction, a world that includes a “speaker, actors, events, and an implied audience” (32).

- Genre describes types of fiction. Important to note, even experts have concluded that the parameters of genre aren’t clearly defined. Culler claims that years of theory fail to “outline the major principles of genre theory” and don’t offer us an exact definition of genre. Rick Altman, author of Film/Genre seems to agree, as evident in the quote below.

“[T]here is no place outside of history from which purely ‘theoretical’ definitions of genre might be made.”

~Rick Altman, Film/Genre

Why care?

The most clear-cut definitions of literary and genre exist in a dictionary. But those definitions don’t help much when querying a manuscript.

In their profiles, agents list the types of work they’re looking for. Sometimes literary sits among a variety of genres. Therefore, we should assume those agents mean literary fiction. Does that mean literary has become a genre itself? Whether is does or doesn’t, querying writers should determine the difference between literary fiction and genre fiction. Although not all agents are “genre purists,” a term Donald Maas uses in Writing 21st Century Fiction, categorizing fiction is a matter of practicality for authors, agents, publishers, and readers.

Authors

An author queries agents looking for the genre of work he writes. He wouldn’t–or shouldn’t– query science fiction to an agent looking for historical fiction. If the author did, he’d come across as amateur. The agent wouldn’t bother reading through the rest of the submission.

Agents and publishers

Agents, like readers, prefer certain genres of literature. They also look for works publishers request. No matter what, agents need to categorize a book in order to pitch it to publishers. Publishers categorize so booksellers know where to shelve the books in the store, or so the book will show up in an online search result for that category of book. Proper categorization leads to sales, which not only maintain the book business but also shed light on supply and demand. If the category is popular, the publisher could put out a call for similar types of manuscripts.

Readers

Individuals have their own unique tastes in literature. They go into Barnes and Noble and ask, “Where can I find contemporary YA action adventure?” or “Where are the cozy mysteries?” If not a brick-and-mortar store, potential book-buyers will enter a category in a search box. Once again, if a book is properly categorized, the likelihood of a purchase increases. Sales mean money—for the store, the publisher, the agent, and the author. Hopefully, and more important, sales satisfy readers in the end.

Blurred lines

Definitions of genre and literary depend on the era in which we live. When it comes to describing what makes a work literary, the answer is prone to subjectivity. Good writers incorporate literary devices into their fiction. Opinion determines how well those devices are composed and whether they complement a work.

Consider again the “literary fiction is character driven and genre fiction is plot driven” philosophy. Alas, the solution to our dilemma isn’t that simple:

A plot can’t drive a story without characters. Decisions must be made, and those involve thinking–a plot can’t think. Nor can it grow emotionally. That being so, theme can’t be delivered without characters contending with whatever the plot throws at them. Plot steers characters. However, characters steer plot. The consequences of their actions or inactions command this.

Literary or genre, readers surmise why the MC makes a decision. They interpret plot to determine the story’s purpose, be it practical, emotional, or spiritual. One reader attaches a memory to an aspect of plot. Another connects emotionally to a character’s decision. Each reader’s unique life experiences and cognitive abilities affect story interpretation.

Jonathan Culler on the literariness of literature

What does literary mean?

Culler, similar to the dictionary, uses the term literary to describe “literature.” This being true, safe to say a literary work is, in fact, literature.

What is literature?

According to Culler, literature is an analyzable story (not the instruction manual of your toaster oven). Readers can apply literary theory to it. They can draw unique conclusions from narratives that don’t deliver a distinct message but rather an abstract one.

Example

Hemingway’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants” isn’t just about a couple waiting for a train, discussing a mysterious topic. The couple discusses abortion without ever saying the word. The man tries to convince the woman, who is pregnant, that the procedure is no big deal. Setting elements beg readers for interpretation, example being contrasting descriptions of landscape. They may foreshadow or represent the woman’s choice, which is never disclosed.

Readers must stew on the possibilities, however grim or happy. Personal experiences and belief systems will influence what readers stew upon and which emotions surface. Attitudes toward the characters and their dialogue will also influence interpretations of symbolism and theme.

Fiction is literary

According to Culler, a literary work is typically “a linguistic event which projects a fictional world that includes speaker, actors, events, and an implied audience” (31-2). Characters are “imagined.” Diectics plays a role too: the meanings of here and now, for example, depend on the context of the story. Thus, a literary work—fiction—requires more attention than your basic toaster manual.

In fiction, readers interpret what the speaker says and form hypotheses about the author’s motivation. And the function of the story depends on the reader’s interpretation of the work. “Fictionality” sets the foundation for interpretation. This makes fiction literary and sets the stage for a universal story. Such an interpretatively malleable story delivers a tale of the “human condition” rather than a mere jaunt through concrete plot.

Example:

As Culler explains, depending on a reader’s interpretation, Shakespeare’s Hamlet could be a story about the history of Denmark, Danish-prince problems, or mother-son problems (a prime subject for the application of Freudian theory). I’d even say the play explores the paranormal and the effects of mental illness. After all, the main character does see apparitions.

Genre

Anyone who prefers a certain type of book already has an idea of what genre is. Many categories exist–odds are most of us don’t know them all. Titles and subtitles of genre pop up as time moves on. However, this doesn’t clarify what literary fiction is, especially because literary fiction also falls into genres.

When Culler and Rick Altman discuss genre as it relates to literary works–fiction–the authors speak of literary and genre theory, not literary fiction and genre fiction.

Culler says fiction works are literary works. One in the same, they are written works whose meanings subject to unique, individual interpretations. Therefore, one can conclude that all literary works can fall into a genre, or category. In fact, Culler describes genre as a “larger structure” of literature, compared to “rhetorical figures” within the story.

Genres unheard of years ago exist now, but that doesn’t mean old works can’t fit into modern-day genre categories and vice versa. Altman gives a historical overview of literary genre, covering points of view over a period of centuries—those of Aristotle, Horace, Northrop Frye, and more, including modern-day genre theorists. Yet outside of that history, as his quote above indicates, a succinct theoretical definition of genre can’t be made. Perspectives on genre change with time and societal changes.

The million-dollar question

If fiction is literary, why do agents list literary as a separate category from genre works? The best way to find out is to ask individual agents what they mean by this, which isn’t necessarily realistic or practical. Although each might view the term differently, agents seek what publishers ask for. So there must be a general consensus in the publishing world regarding the meaning of literary and how that type of literature differs from genre.

A little bit of both

Thinking about my own works, I’ve often wondered, can’t a genre story be literary too? From what I’ve read, the general consensus is: in literary fiction, the main character drives the story (internal struggle); genre fiction is plot-oriented. But don’t all stories need a good plot?

Recently, I read a 2014 New Yorker article by Joshua Rothman that digs deeper into the question. Rothman endorses Northrop Frye’s view of fiction and drama, saying Frye’s “world of fiction is composed of four braided genres: novel, romance, anatomy, and confession.” The article sheds light on how genres can overlap, validating my own feeling on the topic. However, the content isn’t helpful from the perspective of a querying author trying to figure out how to categorize her work using current standards or trends.

All literary fiction could fit into a genre, which can be as broad and classic as romance or as narrow and contemporary as the subgenre steampunk. But can all genre be literary? Judging from agents’ wish lists, I’d say no. However, some genre can be literary. Donald Maas, a New York literary agent, confirms this in Writing 21st Century Fiction. He says some genre works are written so well, they “attain a status and recognition usually reserved for literary works.”

In the past, Maas claims, “strict category telling” served readers and “had sociological appeal.” With that said, he claims his agency cares less about categories and more about how a story affects the reader. Such a story “fulfill[s] the purpose of fiction”—it sucks the reader into a tale that sheds new insight on familiar topics, engaging the reader in a satisfying emotional journey (13). Therefore, if you struggle to categorize your book, fear not. The most important thing is that you present a well-written, captivating story.

“For me, where genre ends and literature begins doesn’t matter. What matters is whether a given novel hits me with high impact.”

Donald Maas, Writing 21st Century Fiction

Literary Fiction Versus Genre Fiction, a practical approach

1.) Push aside Culler’s and the dictionary’s definition of literary. Because when we query agents or market a self-published book, we’re dealing with literary fiction versus genre fiction.

2.) Keep in mind that readers attach expectations to each category of books. When writing a story, be aware of what readers expect of that particular genre–romance, action, fantasy, mystery, horror, etc. Think of what you expect of a certain category of book.

3.) Despite being genre fiction, your work could still eventually move into the literary zone. Therefore, write what you like to write. It will all pan out in the end.

Literary Genre, in general

Consider the following points Rick Altman makes on genre theory, in Chapter One of Film/Genre.

- The function of genre texts can be observed and objectively described.

- Books in any given genre “generate similar readings, similar meanings, and similar uses” (12).

- Genre often reflects the science and “decorum” of the society among which it is created.

- Structure is more complex.

The above points relate to the literary canon, which includes literary fiction and genre fiction. However, readers expect certain experiences from literary fiction and genre fiction. Before a book is even read, the category into which that book was placed primes readers’ minds for these expectations.

Literary fiction

In The Complete Handbook of Novel Writing, 2nd ed., the editors of Writer’s Digest offer insight on what literary writers in particular do.

- According to Donna Levinson, they make careful choices in details to make common experiences new (145).

- Nance Kress says they compensate for a tightly woven, orderly plot by including elements unrelated to the plot. She suggests doing so reflects the disorder of reality. A good story balances the order of a tidy plot and the disorder of life. Literary writers pay closer attention to this by weaving thematic elements into the plot (169).

My two cents

Research and fiction-reading experiences, in general, have impressed upon me that literary fiction contains most or all of the following:

- Complex story structure into which the author weaves psychological, cultural, and/or spiritual themes–abstract, universal themes.

- Sophisticated literary devices that complement action, theme, mood, and character arc. In fact, these devices expose and animate the character’s internal journey throughout the external journey.

- The qualities of what an acquiring agent and/or a reader considers literary fiction. Mindreading skills may help, but so can researching books agents have sold to publishers and what categories those books fall into. Because in the end, an element of subjectivity–the agent’s, acquiring editor’s, reader’s–plays a role in categorizing a work.

- As Donald Maas suggests, a story that follows the plot structure of a genre can be so well written, it can be considered a literary work.

- “Well written” means the work at least includes most of the above points.

“[W]ithin any category, each editor brings particular literary beliefs to the job.”

~Michael Seidman, The Complete Handbook of Novel Writing (2010) [“STUDY THE MARKET!,” Ch. 48]

Two ways of deal with the issue

- Write to market, imitating existing genres and subgenres. Then, you won’t have such a hard time categorizing your book. Ricardo Fayet discusses this in How to Market a Book. Or . . .

- Follow you heart. Break genre barriers. This is how literature progresses.

Conclusion

The general consensus is books need to be categorized. Deciding whether your book is literary or genre fiction comes down to reader expectations, practicality, and money. Those who read thrillers expect suspense. Those who read action adventure expect high-stakes action and an epic journey. People have a variety of tastes. In a bookstore, they beeline it to the bookshelf that holds their genre. This is why literary agents and publishers categorize literature.

Agents and acquiring editors bring their own ideas to the literary-genre debate. Therefore, pay attention to what you read. Note the style of the writing, plot structure, text structure, and literary devices used. Research the category you’re reading. With that said, when you write, dare to break boundaries. You may just find your genre fiction mingling at the literary cocktail party.