Would you love to write a novel but don’t know where to start? Do you fear you’re not good enough to write a novel? If so, this article is for you.

Just as a story has a beginning, middle, and end, so does the process of writing a novel. Here’s how to write your own, starting with the basics and working your way up.

- Give yourself permission to write a novel. If you need it from someone else, here it is: Go for it!

You can write a novel regardless of how old you are or what your education level is. Bad grammar? No worries. Your imagination doesn’t need a degree or perfect language skills. Imagination is a built-in, human feature. Aren’t we lucky?

Whatever your background, write that story itching to get out of your head and onto the paper. You never know where it will take you.

Still not sure you can do it? Read Steven King’s On Writing for a little motivation–I did.

*If you struggle with physical, cognitive, or emotional challenges and don’t already have a system for getting your thoughts into words or an audio file, ask your go-to support for suggestions on how to customize the following steps to your learning and writing style. As the expression goes, Where there’s a will, there’s a way. - Read the genre you’d like to write.

I’ve been reading YA for years because that’s what I write and enjoy. Now that I’ve completed the first draft of my third novel, I’m considering writing middle-grade fiction. Therefore, I’m currently reading the first book in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. As well, I recently took a middle-grade literature college class.

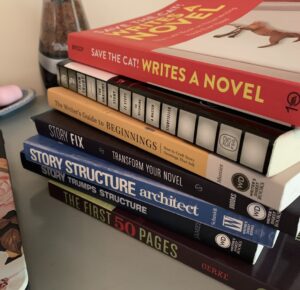

As you write your novel, find time to read one book after the next. Take note of sentence structure and literary tools used, such as repetition, alliteration, rhyme, metaphor, etc. Note action verbs and the level of difficulty of the author’s word choices. Start with popular books in the genre you’re writing. They’re models of what publishers deemed worthy of publishing. - Study story structure. (If you already have, review it.)

Important plot points, or “beats,” drive the story forward. For example, the “inciting incident” catapults the main character out of their usual routine. As well, each genre has specific story elements readers have come to expect–for example, sci-fi readers expect new-world settings, and fantasy readers might want to see out-of-this world events and characters.

While researching story structure, you will probably discover that a story’s beginning, middle, and end should each succeed in accomplishing certain goals. Consider the following:

Beginning

Grip your reader’s attention and set the story’s tone with a first line that packs a punch. Hang on to their attention through action that sets up the story and makes your readers care about your main character, whom you’re about to put through the ringer. Main characters who act tough or like jerks should do at least one thing to show their soft side, making them likable. For instance, in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, Katniss acts tough, but she coddles her sister, and she spares the cat she doesn’t like, even though she and her family are starving. End the beginning, or Act I, with an inciting incident, such as when Katniss volunteers to take her sister’s place at the Hunger Games.

Tip: Don’t start your story with:

(1) a dream sequence (cliché and a waste of your readers time)

(2) your main character getting out of bed (cliché)

(3) a preachy rant by the narrator

(4) long-winded descriptions

*The last two hold true for the rest of the book as well.

Middle

Show your main character(s) exploring their new world, such as when Katniss sits at tables loaded with food, when she trains for the games, interviews, and hurdles physical and emotional obstacles during the games. Introduce a “B-story,” maybe a romance but nevertheless an underlying, less important plot line. This will add depth to the main story line and eventually merge with it at the midpoint, where the main character(s) may experience a false victory or defeat. Maintaining your readers’ interest can be challenging.

Tip: Dos and Don’ts

*Do give readers a tension break if the story is sensational or suspenseful, especially if those in the middle grade and younger.

*Look at low-key scenes objectively. Would you snooze through it if this were someone else’s work? If so, spice it up.

*Research to add substance to your content and (hopefully) spark exciting ideas.

*Don’t write everything you’ve learned from your research. This could overwhelm or bore your readers. Pepper necessary information into the story where appropriate.

*As noted above, don’t be “preachy.” Readers can think for themselves. Show your message through story–action, dialogue, symbolism, etc.

End

Up the tension as your story rises to the climax: Your main character suffers a blow. They’re thinking all is lost, sometimes referred to as the “dark night of the soul.” In The Hunger Games, Katniss’s all-is-lost moment is when Rue dies.

Next, the main character has a “Eureka” moment, which helps them fit the pieces of the story “puzzle” together. This leads to a final resolution–problem solved. I’d say Katniss’s eureka moment is when the announcer says two people can survive the games, so long as they are from the same district. Katniss realizes if she finds Peta alive, they both can win the games.

End with a final image readers will relish. If you think you might write a sequel, satisfy readers but don’t etch in stone a final destination for your main characters. Maybe they’ll wonder What now?, which is what Peta asks Katniss on their way back to District Twelve–a great set-up for a sequel.

Read more: See my article “Conflict” to learn about its importance. Check out Les Edgarton’s book Hooked, which elaborates on the concept, especially as it relates to story beginnings. - Set aside time to write.

Choose a time frame that gives you the most “me time.” This may be exhausting at first, but whether you have to wake up at five in the morning or start writing at ten at night, decide. Your success depends on it.

- Build a foundation for the story you will write.

First, answer this question in one sentence: What is your story about?Also known as a “logline,” this description should include who (the protagonist), what (the problem), where, and the problem (caused by an antagonist). As well, it should include action verbs. Obviously, this is easier if you already have a story in mind.

Using my novel The Breakheart Militia as an example:

“Eighteen-year-old Wade Hendrick dreams of escaping Altamont’s violent drama but must confront it when an ornery general calls him for help after being shot by rogue troops.”

Next, take the above statement a step further by explaining the point of the story.

Knowing key “beats” of your story makes this task easier. (Jessica Brody’s Save the Cat! Writes a Novel explains in depth, as I point out in my Nutshell Review.) If you don’t know yet, imagine the story you have in mind playing out. Or think of a book blurb, the book-cover description that baits readers, It doesn’t give away the end, and it hints at theme. If you can do this, writing the story will be easier, as you’ll have a better idea of where the story is going and what the main themes are.

I didn’t attempt to write a “blurb” until I finished my first novel, but I wish I’d tried beforehand. This description is subject to change, but it’s a starting point.

Example:

The Breakheart Militia

Eighteen-year-old Wade Hendrick plans to escape Altamont’s violent drama but must confront it when an ornery general calls for help after being shot. Catapulted into a lethal game of whack-a-mole, Wade seeks help from Al McCoy, an aging, once elusive ally, who owns the property known as Castle Hill. Here, a mansion sits above ground and a massive cave below, a homey mega-grotto Wade and his friends hide out in when they’re not sneaking off or battling strikers. The teens and their allies are targets because of their affiliation with Camp Allegiance, part of an underground military network gathering intelligence in an effort to oust President Malicoat, a murderous agent of “Gloco,” a global entity hell bent on taking down America. Rescue runs with the general and Al have Wade developing a yen for helping people, a task he prefers to killing them. And while death and destruction take their toll on Wade’s ability to trust, the experience might just reconnect the teen with love and a sense of home in the city that claimed his mother’s life.

*Notice how I’ve expanded the idea of my original logline, creating a piece similar to a book blurb–it describes the inciting incident, where the story goes, and reflects important themes.

Not quite there yet? Don’t be discouraged. Read on. - Write your novel.

If you completed the tasks in #5, congrats, you’ve already begun. If you weren’t able to, it’s okay. Try this: write three sentences describing the beginning, middle, and end of a story you’d like to write. This provides a foundation for your work. Again, these are subject to change. Below I again draw examples from my first novel:

The Breakheart Militia

Describe the beginning: Surface problem: Wade plans to leave Altamont in a year, but he’s forced to put his masterplan on hold after his father leaves on a mission and General Fox calls him for help. Internal conflict: Wade wants to escape because the uncertainty that goes with life in Altamont stresses him out.

Describe the middle: Wade and his friends must live in (and under) Castle Hill, home of a newly discovered, aging ally, where he and his friends battle insurgents–Wade occasionally sneaks out, upping the excitement. B-story: Wade learns more about his love interest’s family life, which helps him understand her better. Internal conflict arcs, and he realizes the mental ingredient required to deal with uncertainty. He still wonders whether that “ingredient” is always there inside him or only sometimes.

Describe the end: Wade’s adventure forces him to take another look at the town he calls home, where his mother was killed and where he’s not only loved but can make a difference. Wade understands the secret behind that special ingredient that would make a person want to live in an unstable city like Altamont.

elaborate on each. To do so, you may have to ask yourself questions:

Why is your character here/how did they get there?

What does your character want to do?

What does your character need to do if they are to change for the better?

Include the answers in your story–but do it in a creative way. Work the ins and outs of your characters not just through description, or “telling,” but through “showing” and dialogue. Telling too much makes for a boring read.

Pick a narrator. Whose point of view are you telling the story from? I tell The Breakheart Militia from the main character’s POV.

Pick a tense. I started my story in past tense but changed it to present, which I found easier to write and complementary to my story.

How long should your novel be?

General rules, as noted in an article by Masterclass (see my Nutshell Review here) is as follows:

children (7-8 years old): 1K-10K words

middle grade (8-12 years old): 20K-50K words

young adult: 40K-80K (Science fiction would be at the higher end.)

adult: 80K-100K words. Scifi could be as high as 120K.

*The above ranges are guides. You’re first draft may be way over the range, but as you edit it the number will probably come down, especially if you hire a professional editor.

How long should your chapters be?

Chapter lengths vary–shorter chapters for younger readers; longer for older kids and up. Chapter length is also subject to unique formats, or style. An author (you) may have a story-telling reason for the length of your chapters, each of which often, but not always, depicts a single scene.

Still Staring at a blank Page?

Read my article on Ernest Hemingway’s strategy for tackling the blank page. One true sentence could get you rolling.

Stuck in the middle of your story?

Research what you need to know about specifics in your story, be they about setting, character traits (look in psychology magazines), technology, professions, hobbies, or whatever you deem relevant. This is what I do when I get stuck on where to go with plot or how I can create figurative imagery. Information you discover may spawn new ideas or imagery-evoking metaphors that help hold readers’ attention. And speaking of imagery and metaphors . . .

- Add flare to your writing.

–Use literary devices.This is the fun, yet still challenging, part. Figurative language, such as metaphors, symbolism, and similes, spark imagery. Action verbs and alliteration improve reading flow and make the read more appealing. If at first you’re at a loss for such words, just get the story down in a first draft–you can always make the changes in future drafts.

Tip: Purdue Online Writing lab explains common literary terms.

—Create a great first line.

Now that you know your characters and story better, go back and look at your first line. If you were in a book store, would it lure you to read more? Go in the book store one day. Take a look at first lines of successful books to get an idea of a good first lines. While you’re at it, read the blurbs to learn what makes a good one.

Tip: This is more of a reminder about Step 2. The more you read, the better you’ll understand what constitutes a great first line and brilliant, image-evoking sentences. - After you finish your story, take about six weeks off from it.

Taking a break refreshes your eyes for the next time you read through it, helping you pick up on plot holes, inconsistencies, etc. Continue to read and start another work if you wish–you’ll be all the wiser when you revisit your novel, thus better equipped to edit and self-critique.

- After the break from your novel, re-read it, taking notes on consistency and plot holes.

Make sure your characters hair and eyes don’t change unless morphing is their thing. Make sure plot elements come together in the end like pieces of a puzzle, forming the whole picture. Did you answer important questions readers will want to know? Did you make sure that where your characters are and what they’re doing make sense? For example, would it be possible for them to be at point B if their car broke down at point A?

- Check for overused words and vague words.

Take advantage of your writing software’s search tool to find such words.

Examples:

something–If you use something, replace it with specifics. What is that something?

just

but

and

really (and other adverbs)–Avoid adverbs whenever possible.

probably

I

you

and

when

literally

[And so on]

Get creative: Replace adverbs and adjectives with metaphors and similes that describe the noun or plot element. - Correct misspelled words, errors that many people make in the heat of the moment.

Again, use your search tool to find and correct these common errors.

Examples:

your vs. you’re

its vs. it’s

lie vs. lay; lay vs. laid

insure, ensure, assure

whether, weather

Resources for word usage:

Section 5.250 of The Chicago Manual of Style lists a “Glossary of Problematic Words and Phrases.”

In The Elements of Style William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White briefly addresses a variety of grammar and style issues–a handy guide for those just learning how to write. - Take editing as far as you can take it.

I researched grammatical questions online, took a grammar and style class in college, and I bought a Chicago Manual of Style. However you decide to get answers to your grammar and style questions, make your manuscript is as error-free and tight as possible before you query and/or seek a professional editor:

*Cut out redundancies (e.g., “long-winded rant”–no. Rants are long-winded.)

*Check capitalization & punctuation–limit exclamation-mark use.

*Italicize thoughts & names of books.

*Change passive verbs to active verbs.

*If you write in first person, make sure your don’t “head jump.” Your main character can’t read minds unless you clarify they’re psychic.

If you’re not confident with your writing skills, join a writing group or ask classmates, teachers, or friends who can be objective to critique your work and/or help you with your writing issues.

*No matter how well you know grammar and style, hire a professional proofreader if you plan to self-publish. (Read more about this in Step 13.) Everyone makes typos. Even after comprehensive editing, errors still can lurk. Recently, an editor I hired to copyedit my first novel found a “you’re/your” typo despite my previous efforts of searching for and correcting that particular error. - Once you’ve gotten to the point where you feel as though you can’t edit anymore and you’ve gone through that you’re work is as clean and tight as you can get it, congratulations! You’ve written a novel, and that’s a grand accomplishment. But you’re not quite done, especially if you plan to publish it.

IF YOU PLAN TO QUERY A LITERARY AGENT

–Hire or recruit trusted Beta Readers

They can offer insight on where they get confused or lost, as well as point out consistency problems, plot holes, and typos. Beta readers can be friends, peers, professors–anyone you trust to be objective (honest, tells the dirty truth about what needs improvement).

*Don’t down yourself if they pick up on plot holes or inconsistencies you didn’t pick up on.

–Research agents interested in your book’s genre.

This process deserves its own How To, which I plan to get to soon. An agent who takes you on will likely edit and/or provide editors for your book, which is good because you won’t have to pay for it!

If you plan to self-publish

Hire a professional editor.

Editing is a process in and of itself. Books on the shelves of Barnes and Noble have gone through several editing processes, and so should your novel. Types of editing include developmental editing, copyediting, and proofreading. (I found a copyeditor on Reedsy).

A copyedit is comprehensive, and the copyeditor does proofread, but this first professional edit will likely not be enough. You will make more typos and need more editorial insight after you’ve made edits based on the professional’s edits. Even if that editor takes another look at your work, consider hiring a different proofreader before self-publishing. A fresh set of eyes will pick up on missed typos.

Writing is a craft that requires honing and a process as unique as each writer. Consider what you learn here and elsewhere, but do what works best for you. Different experts describe plot points differently, just as different writers approach novel writing differently. As you explore the How Tos of writing, you’ll figure out which approach works best for you. (“Pantsers” write off the top of their heads. “Plotters” outline the plot. I do both with the help of Scrivener writing software, a good fit for my writing style. Read my Scrivener review here.)

Whatever you choose to do in the end with your novel, remember: you have to write it first. I hope my How To pointers help guide you along. Happy writing!

Read more: take a look at how I went about writing my first novel.